Pearl is unique among the birthstones inasmuch as it is of organic origin. All other birthstones are minerals, inorganic solid substances with crystalline structures and fixed chemical compositions that vary only within rigid limits. Pearl are made up of little overlapping platelets of the mineral aragonite, a calcium carbonate that crystallizes in the orthorhombic system. Although the pearl itself is made up of a mineral, its organic origin excludes it from being included with minerals. Pearls have a fairly long geologic history---the oldest examples have been recorded from rocks of Triassic age in Hungary and the Cretaceous age in California but all had lost their luster. The oldest pearls with luster have been recorded from rocks of Eocene age in southern England.

Pearl is also unique inasmuch as it is probably the only gem material that can be utilized in jewelry immediately upon finding one. All other gems need to be fashioned and polished, however crudely, before they are set in jewelry. Pearls were exceedingly popular in Roman times and were cherished by Byzantine royalty. Robes and cloaks of the royalty may have been studded with thousands of pearls.

Pearls form in either salt or fresh water environments in several species of bivalves (clams) that are members of the Phylum Mollusca. The mollusk body plan involves a head, a foot, a visceral mass and mantle lobes that are carried about in a hard, calcium carbonate (calcite or aragonite) shell. Historically most of the pearls that were used in the jewelry trade came from the marine bivalves Pinctada vulgaris and P. margaratifera that were abundant in the Persian Gulf. The environmental conditions for these bivalves were ideal---the basin is about 15 - 20 m deep except for in its center. Divers who worked with small crews from small boats recovered the clams. When the pearl was recovered it was cleaned of mud and any organic matter. The pearl divers sold their harvest to dealers who delivered them to brokers in India who then bleached them of any stains with hydrogen peroxide. The pearls were size-sorted and graded and most were sold to dealers in Western Europe, mostly in Paris.

Fresh water pearls have been found in several species of clams that inhabit rivers in the United States. Most of these have been related to species of Unio and these are now becoming the basis of a fresh water cultured pearl industry in parts of the United States. Pearls form when an irritant becomes lodged between the mantle lobe and shell of the bivalve. The bivalve secretes layers of aragonite platelets around the irritant and this forms the pearl. If everything goes perfectly, the pearl nucleus will become separated from the shell and become completely surrounded by the mantle and the resultant growth will be a loose and spherical pearl. In some cases the nucleus does not become separated from the shell and the result is pearly blister on the inside of the shell. In cross section a pearl will appear to have concentric, smooth layers, but magnification will show these layers have an imbricate (brick wall-like) structure. These tiny plates are held together by an organic cementing agent called conchiolin. Magnification of the surface will show irregular lines that resemble topographic contours. The pearl derives its iridescence from the diffraction and interference of white light that is caused by the tiny overlapping platelets of calcium carbonate. The iridescence or orient of the pearl is a function of the numbers and thickness of these platelets. Mother of pearl or nacre forms on the inner walls or inner surfaces of the mollusk shell. Mother of pearl differs from pearl inasmuch as it is part of the mollusk shell whereas the pearl has become a separate entity from the shell.

Several factors influence the value of pearl and these include color, luster, iridescence, shape, and size.

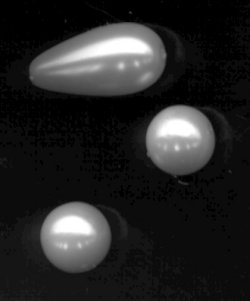

Large, spherical pearls are the most desired and fine examples can command very high prices. Popularity of pearl colors varies from place to place and culture to culture. Cream rose' and light rose colors are almost universally liked and pure white or pure yellow pearls are almost universally disliked but the many shades in between enjoy higher or lower status in various places in the world. Oblong, tear drop or flat pearls usually command lower premiums. Semi-translucent pearls with high luster are more desired than opaque pearls with low luster. Orient or iridescence are also very important in grading pearls. Strings of pearls are graded not only on the above criteria but also how well the colors and luster of the individual pearls match in the total piece.

Pearl substitutes have been made from various resins and plastics and some are quite attractive though nearly valueless. These usually have a much lower specific gravity than the natural or cultured pearl. The gemologist's problem is usually that of determining whether a pearl or strand of pearls is natural or cultured.

A cultured pearl is made by inserting a rounded bead of clam shell between the shell and mantle of the oyster. These beads were formerly manufactured in Muscatine, Iowa, where a large pearl button industry once flourished. The pearl culturing industry was pioneered in Japan where oysters of the species Pinctada martensii serve as hosts. The bead is inserted in oysters that are about three years old. The oysters are harvested in one to two years and the pearls are removed. The oyster secretes calcium carbonate around the bead at a rate ranging from about 0.1 to 0.2 mm per year. Although pearl farming began in Japan, the industry has spread to parts of Australia and American companies are working with culturing fresh water pearls.

The only sure way to separate a natural from a cultured pearl is by X-ray. Rubbing the pearls across the teeth, by candling them, or using tests such as specific gravity can not make such separations.

Care of pearls is very important. Pearls can be easily discolored from skin oils. Properly strung pearls will have a knot between each pearl to keep them from rubbing together. The cultured pearl can be damaged by excessive wear that exposes the non-gem nucleus.

References

- Moore, R. C., 1969. [Editor] Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part N, v. 1 (of 3) MOLLUSCA 6 Bivalvia, p. 78.

- Peach, J. L., Sr., 1999. Freshwater Pearls: New Millenium-New Pearl Order. [Abstract] International Gemological Symposium, Symposium Program, San Diego, June 21-24, 1999, p. 15, 16.

- Schumann, W., 1977. Gemstones of the World. Sterling Publishing Company, New York, 226 p.

- Shipley, R. M., 1971. Dictionary of Gems and Gemology. Sixth Edition. Gemological Institute of America, Los Angeles, California, 230 p.

- Sinkankas, J., 1959. Gemstones of North America. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, 675 p.