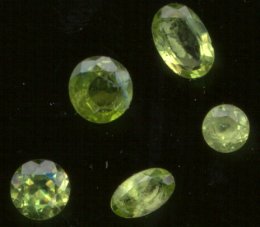

If you were born in the Month of August, your birthstone is peridot (pronounced: pair-uh-dough), a transparent yellowish-green, Magnesium/Iron Silicate. Peridot is actually a gem variety of the mineral Chrysolite or Olivene and its chemical formula is given by: (Mg,Fe)2SiO4.

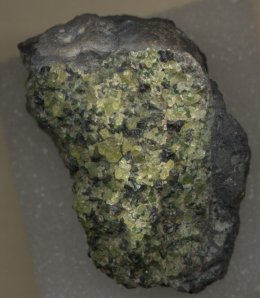

The ratio of Magnesium and Iron in the crystal is highly variable and the name Forsterite (Fo) is applied to Magnesium-rich/Iron-poor crystals whereas the name Fayalite (Fa) is applied to Magnesium-poor/Iron-rich crystals. Sometimes the formula may be expressed as some ratio such as Fo44/Fa56 for an example that is 44% Magnesium Silicate and 56% Iron Silicate. For gemoligic purposes, the (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 formula is entirely useable. Crystals are often flattened and much peridot is found in granular masses or embedded grains in a finer grained basic igneous rock such as basalt or gabbro. Peridot has a distinct cleavage (breakage along preferred planes) and a conchoidal (shell-like) fracture. It ranges from about 6.5 to 7 on Mohs hardness scale. Peridot is fairly dense with a specific gravity (weight of the crystal compared to the weight of an equal volume of water) ranging from about 3.27 to 3.37.

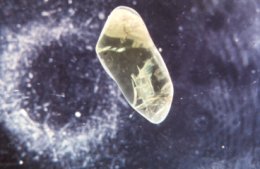

Peridot crystallizes in the orthorhombic system---there three crystallographic axes that are perpendicular to one another but all are of different lengths. Orthorhombic crystals have two non-crystallographic axes along which light travels at fixed velocities. These are called optic axes and since there are two, orthorhombic crystals are said to be biaxial. The refractive indexes (the numerical measures of how much a light beam is bent and slowed down when it enters a substance) of peridot range from about 1.654 to 1.690. Peridot has three refractive indexes, two of which remain fixed and one that is variable and numerically between the upper and lower index.

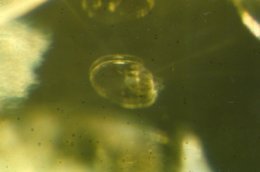

The birefringence (numerical difference between the highest and lowest refractive indexes)of peridot is fairly high: 1.690 - 1.654 = 0.036. What this tells us is that when a beam of light enters the crystal, it is refracted (bent and slowed down) such that whatever is viewed through the crystal is seen as a split image. This fact is very valuable to the jeweler or gemologist for when one views a faceted peridot through the table of the stone, the junctions of adjacent facets are strongly doubled. Inclusions in peridot are also strongly doubled. Peridot may have small inclusions of biotite (brown), chromite (black), pyrope garnet (dark red), spinel (tiny octahedra) or liquid and gas-filled inclusions that resemble fried eggs. The strong doubling of facet junctions and inclusions as well as the pale yellowish green color are very characteristic of peridot.

Common substitutes for peridot include synthetic sapphire and synthetic spinel. Both of these are isotropic (have but one refractive index) and doubling will not be observed. Glass will show some elongated bubbles and no doubling.

Historically, the use of peridot goes back several thousands of years. Egyptians enslaved the people of St. John's Island in the Red Sea and forced them to mine peridot for use in ornaments and jewelry. Fine gem peridot has also been mined near Mogok, Burma, and Minas Gerais, Brazil. Some fine gem peridot has recently been found in Pakistan. Volcanic bombs containing small peridot crystals of nice gem quality have been found in basaltic rocks New Mexico and Arizona. The San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona has yielded numerous stones that are in the 4 to 5 carat range as uncut rough. Historically, most peridots have small and few finished stones larger than 10 or 15 carats in weight were available. In recent times, some large finished stones from Myanmar in the 40 to 50 carat weight range were recorded. The Pakistan sources have produced some stones weighing over 100 carats and a very large stone that weighed over 300 carats.

For Further Reading

- Ford, W. E., 1958. Dana's Textbook of Mineralogy. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 851 p.

- Kammerling, R. C., Koivula, J. I., and Fritsch, E., 1994. Miscellaneous notes on peridot. In Gem News, Gems and Gemology, Spring, 1994, p. 53.

- Kammerling, R. C., Koivula, J. I., and Fritsch, E., 1995. Miscellaneous notes on peridot. In Gem News, Gems and Gemology, Spring, 1995, p. 62.

- Liddicoat, R. T., Jr., 1969. Handbook of Gem Identification. Gemological Institute of America, Los Angeles, California, 430 p.

- Schumann, W., 1977. Gemstones of the World. Sterling Publishing Co., New York, 256 p.

- Shipley, R. M., 1971. Dictionary of Gems and Gemology. Gemological Institute of America, Los Angeles, CA, 230 p.

- Zeitner, J. C., 1996. Gem and Lapidary Materials for Cutters, Collectors, and Jewelers. Geoscience Press, Tucson, AZ, 347 p.