Ruby celebrates the birthday of those born in the Month of July. The ancient lapidaries (books that described the physical and metaphysical aspects of gems) spend considerable time with ruby. "Those be rubies, fairy favors:" a line from Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream provided the theme for Lincoln (Nebraska) Gem and Mineral Club's 40th anniversary show in 1998. Shakespeare mentioned rubies several times in his various writings and you are referred to the classic reference by George Frederick Kunz for the remainder of these. So not only is ruby the stone to celebrate July's births but it is also the stone to celebrate the 40th anniversary of special occasions.

Fine rubies are probably one of the world's rarest gems. If you were to walk into any jewelry store, the jeweler could probably show you many fine diamonds but probably only a few fine rubies.

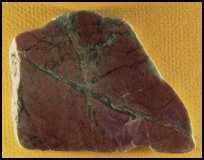

Rubies are a red to orange-red to purple-red variety of the mineral corundum, aluminum oxide (Al2O3). Ruby and its companion variety of corundum, sapphire, are very hard---9 on Mohs scale of 10. Only diamonds and a few manufactured abrasives such as boron carbide and silicon carbide are harder.

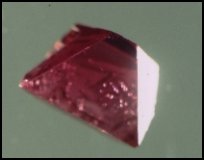

Ruby crystallizes in the hexagonal system---well-formed crystals often appear to be tiny barrels. There are three crystallographic axes of equal length that intersect one another at 120o and a fourth longer axis that is perpendicular to the other three. Ruby as all other varieties of corundum is very tough. It shows no cleavage but the crystals sometimes exhibit a basal parting. Rubies are fairly dense---the specific gravity ranges from 3.95 to 4.10 but most is almost exactly 4.00.

Because of its high specific gravity rubies that come from alluvial sources such as Sri Lanka and Burma are collected in a deep cone-like separator. Gravel and water are placed in the cone and the cone is rotated. Minerals with low specific gravity such as quartz, mica and calcite wash out of the cone as it is rotated. The miner will finish with an aggregate of higher specific gravity minerals near the vertex of the cone. If the miner is fortunate, a few of these stones might prove to be rubies. Red spinel may also be included in these heavy minerals but they are easily separated from ruby by both physical and optical properties.

Since ruby crystallizes in the hexagonal system it has two refractive indexes, the numerical measures of how much a beam of light is refracted (bent) and slowed down when it enters the crystal. These range from the extraordinary ray (the one that varies) of 1.762 on the low end to the ordinary ray (the one that remains fixed) of 1.770 on the high end. Since the stone has only one index of refraction that remains fixed (the optic axis), it is said to be uniaxial. Since the lower refractive index varies upward to meet the higher, the stone is said to be negative. Ruby is said to be uniaxial negative.

Rubies may be dichroic---that is, one wavelength of light is transmitted along a crystallographic axis while another wavelength may be absorbed along the same axis. A small instrument called a dichroscope is needed to detect dichroism. A dichroscope may be made with a pair of calcite prisms that are oriented to take advantage of the strong birefringence (numerical differences in refractive indexes) of this mineral. One of the calcite prisms will transmit a certain wavelength and the other will absorb it. Thus, the viewer sees two different colors in the two windows of the dichroscope. A simple dichroscope can be constructed by orienting two pieces of polaroid material perpendicular to one another. The Polaroid separates the two beams just like the calcite prisms do.

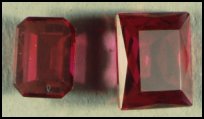

Color is the most important character of a ruby when it comes to a jeweler properly representing the stone. All rubies must be shades of red, orange- red, or purple red. There is no such thing as a pink ruby. By definition pink corundum is a sapphire. There are standard color sets such as those manufactured by PantoneTM that will guide the jeweler or hobbyist in determining where rubies leave off and where sapphires begin so far as color is concerned. I utilize such a set in my gem stone classes at UN-L. It quickly clears up any distinctions for the students.

There are not many stones that can be confused with a ruby (spinel has a much lower RI and tourmaline is strongly doubly refractive) and the biggest problem the jeweler or hobbyist usually faces with these stones is separating the natural from the synthetic stone. In earlier times all of the synthetic rubies were made by the flame fusion process where powdered aluminum was passed through a very hot gas flame. The Aluminum melted and combined with Oxygen to produce synthetic corundum. These stones all had curved growth lines, gas bubbles and flecks of aluminum powder in them. They were easy to spot. Such is not the case now. There are some synthetic (now called created) rubies that are grown in bombs or crucibles of various kinds that are much more difficult to detect. Diffusion treatment may impart a red to colorless or pale corundum.

KashanTM rubies are a flame grown form---as I write this I am looking at an example with veils, step-like and rhomboid crystal inclusions. DourosTM synthetic rubies are produced in Greece and have been marketed only since about 1995. I recently obtained a piece of ChakravortyTM ruby with only the word of the dealer telling me that it contains about 15% natural ruby.

The pages of the last decade of Gems and Gemology and its 15 year Index (1996) show many kinds of synthetic rubies, as well as other gems, have come onto the market. Gemological Institute of America now offers a course on detecting natural, synthetic and treated gems. Where curved growth lines and bubbles once sufficed to separate a natural from a synthetic ruby, new technologies have now forced the jeweler and the hobbyist to learn a whole new set of skills to determine the nature of the stone.

For Further Reading

- Koivula, J. L., Kammerling, R. C., and Fritsch, E., (Editors) 1994. Douros synthetic rubies. Gems and Gemology, Spring 1994, p. 57. -

- ---, 1995. Faceted Kashan synthetic rubies and sapphires. Ibid., Spring 1995, p. 70. Kunz, G. F., 1916. Shakespeare and precious stones...J.B. Lippincot Co., Philadelphia, 100 p.

- McClure, S. F., Kammerling, R. C., and Fritsch, E., 1993. Update on Diffusion-Treated Corundum: Red and Other Colors. Gems and Gemology, v. 29, Spring, p. 16-28.

- Schumann, W., 1977. Gemstones of the World. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., New York, 256 p.

- Stockton, C. M., (Editor), 1996. Gems and Gemology, Fifteen Year Index, 1981-1985. Gemological Institute of America, Santa Monica and Carlsbad, California, 50 p.