Posted: 5/23/2025

Nebraska scientists reveal invisible effects of prairie management practices

By Ronica Stromberg

Well-managed grasslands offer benefits invisible to the human eye, including increased productivity and cooler temperatures, Nebraska scientists say in the May issue of New Phytologist.

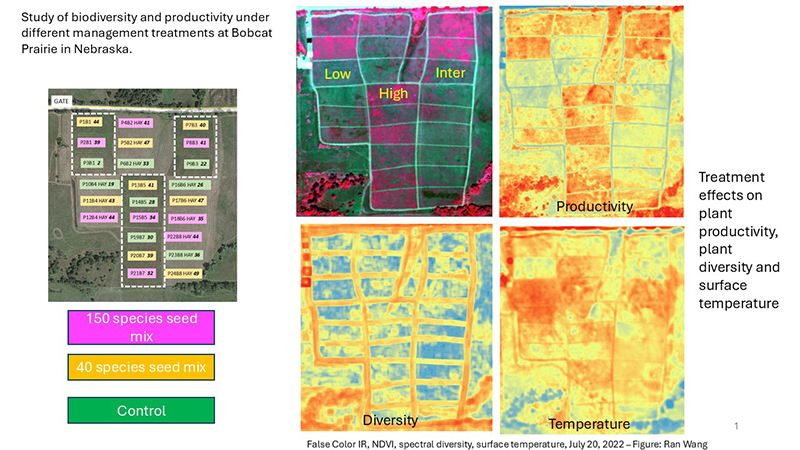

Researchers David Wedin and Katharine Hogan planted diverse seed mixes on 24 plots of land at Bobcat Prairie south of Lincoln in 2018 and 2019. The research team then managed the plots with different combinations of fire, haying, mowing or lying fallow. In July 2022, remote-sensing scientists Ran Wang and John Gamon used spectrometers and thermal imagers to compare the plots with one another and baseline images taken in 2019.

The remote sensing showed that management techniques like planting diverse seed mix and burning and haying improved the prairie's plant diversity, productivity and microclimate.

"And from this imagery and from this set of the data, we saw that they are interconnected," Wang said.

The plots planted with more diverse plants and burned and hayed or mowed grew better and had lower temperatures. Gamon said that might be because they reflected more light and heat and retained more moisture, in addition to absorbing more carbon dioxide from the air. The equipment showed the plants had higher reflectivity, meaning they didn’t absorb as much of the sun’s heat and stayed cooler. Even burned plots, although temporarily hot, showed reduced cooling compared with other plots the next growing season.

"We are pretty sure we are seeing something really exciting," Wang said and noted the study's potential importance to the Conservation Reserve Program.

CRP has been paying farmers, ranchers and landowners to conserve land since the late 1980s. Wang said research on the federal program's results typically focuses on productivity or biodiversity instead of both of these measures and climate concerns also, as the Nebraska study did.

Wang said looking at multiple measures is really hard to do, especially at large scales. Research teams need to fly a plane over plots to gather aerial images, and the high cost of plane use can limit flights to one a year or fewer. A ground crew is also needed to collect data on foot and calibrate the aerial images.

Then, too, Wang said CRP land or restored grasslands are often on private land where scientists are not allowed to track data. Even if the scientists receive permission, landowners paid to plant grass through CRP may plant only one type. Wang said he thought the team was lucky to accomplish what they did.

"The key point we want to illustrate in this manuscript is, we have this technological method that we can use to evaluate grassland restoration efforts," he said.

Gamon said the study also points up the importance of nature-based solutions in restoring and maintaining grasslands. Researchers saw that even without investing a lot of money in the grassland restoration, they could increase biodiversity and productivity and lower surface temperatures, he said.

"The interesting thing is that these things, at least in this experiment, seem to go together," he said. "It points toward the benefits of managing or restoring grassland in such a way to enhance not only biodiversity and conservation value but also productivity and carbon sequestration and climate mitigation. So, it's kind of a win-win-win situation."

He cautioned that this data came from only one site and two flights and said the team wants to gather data from more sites for repeated years and more frequently throughout the year. Wang said the goal would be to fly three times a year, early in the season to catch the peak growth stage of cool season grasses, late in the season to catch the peak growth of warm season grasses and once in between to catch the transition between the grasses.

Gamon said they also want, in future studies, to look at the greenhouse gases of methane and nitrous oxide besides carbon dioxide.

"What we're trying to do with the remote sensing team is put this in the context of the entire ecosystem," he said. "Not just what is this greenhouse gas doing or this other greenhouse gas doing, but how is the whole ecosystem affected by a particular management treatment? So, rotational grazing, burning, fertilizing, irrigation, any of these things that people do in grazing lands."

Grasslands cover about 40 percent of the world's land, and the researchers have yet to see whether results vary from one place to the next. Gamon said that every year, plants take up about a third of the carbon dioxide earth’s inhabitants put into the air so activities on the land that could alter the carbon dioxide output could have a huge impact on the planet.

"If we did this study across all the Great Plains at many different sites and we could replicate this, I think it would tell us that answer of how much cooling effect of the climate can we get from better management of grasslands," he said.

The researchers worked with The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund, ranchers and farmers on the university-funded study and stated plans to continue in this line of research with these partners and researchers at Barta Brothers Ranch. Wang said they also have a NASA project with Oklahoma State University to use ground data and hyperspectral and lidar data to connect everything from below-ground bacteria, to grass, to drone, to airplane, to satellite.

While human eyes can see only part of the solar spectrum, Gamon said the tools they use allow them to see and discover what is invisible on the land.

"We see things that humans can see, but we also see things that are invisible to our eyes," he said. "And when we make the measurements across the full spectrum, that's when we can get the most meaningful measure. Sometimes it's rather remarkable, because what you think you see in your eyes is not what's happening across the whole spectrum.”