Posted: 10/1/2025

Mesonet environmental monitoring capabilities increasing in Nebraska

By Ronica Stromberg

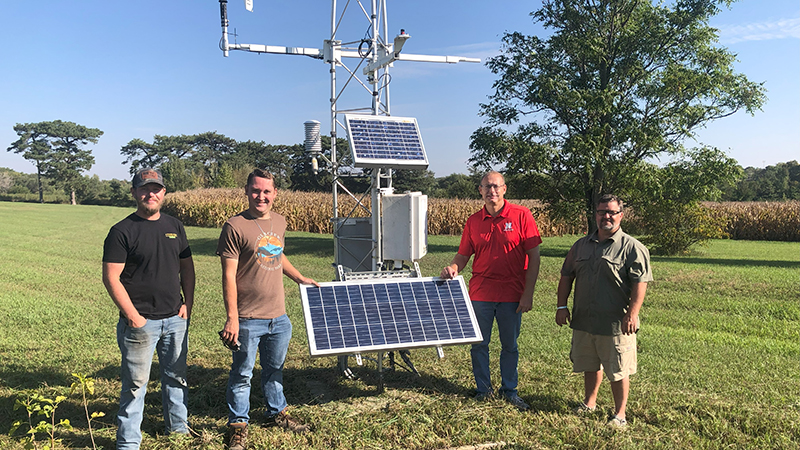

The University of Nebraska–Lincoln is adding 21 weather stations to the Nebraska Mesonet network this year with $1.48 million from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, USDA Farm Service Agency and the Lower Loup and Upper Elkhorn Natural Resource Districts. Ruben Behnke, manager of the Nebraska Mesonet, said the added stations will bring the state's total to 94 and he would like to double that to 200 in the next few years.

"To properly cover the state, you need a relatively dense network," he said. "Otherwise, you're providing data that's not appropriate to people who are trying to put water on their crops. Even more financially important is applying for financial disaster relief through the Farm Service Agency for drought, flood, hail or other disaster."

Farmers are the primary users of the Nebraska Mesonet, often using data from the weather stations to decide when and how much to irrigate and when to plant, spray and harvest. They can learn current conditions and fill out a form to request data at https://nemesonet.unl.edu. Besides measuring weather and climate factors like temperature, precipitation, humidity, solar radiation and wind speed, the stations have buried sensors that measure soil temperature and moisture.

Curtis Gotschall, who runs a cow-calf operation near Atkinson, Nebraska, said he uses rainfall information from the Mesonet for drought assistance. As a board member of the Upper Elkhorn Natural Resources District, he said he has seen the value of Mesonet data for farmers who irrigate and the area could use more stations.

"The weather varies a lot within the area, and I feel it might be important to have more weather stations to the west," he said. "We don't have very many out here in this area."

Governmental agencies such as the Army Corps of Engineers, Farm Service Agency, the USDA, the Nebraska Forest Service, Nebraska Natural Resources Districts and the Nebraska Emergency Management Agency use Nebraska Mesonet data in making decisions on the land. For example, the Nebraska Emergency Management Agency may use the data to predict flooding or drought or may use the historical data to verify landowner claims of damage from weather.

Nebraska first installed five Mesonet stations in 1981, and those offer the oldest data. Each station can gather weather and climate data for up to 20 kilometers around it. To gather data from all parts of the state and be relevant to all users, more stations are needed.

The northern central part of Nebraska has lacked Mesonet weather stations, but Behnke said the area is receiving weather stations through the Army Corps of Engineers funding. The corps funds are supporting 540 installations in the Upper Missouri River Basin, which underlies parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana and Nebraska. Behnke said the additional stations throughout the basin will provide more measurements of precipitation, soil moisture and weather conditions to better model flooding potential.

Behnke and his team of three full-time technicians are also working on developing other tools, such as to detect wildfire risks and to determine the best days to spray herbicides and pesticides so as to not harm a neighbor's crops or livestock.

John Erixson, Nebraska state forester, said the Nebraska Forest Service relies heavily on Mesonet data in protecting and restoring the state’s forests and rangelands.

"During an active wildfire, real-time weather data is essential for firefighter safety and for making tactical decisions," he said. "Rapid changes in wind speed or direction can dramatically alter fire behavior, potentially endangering crews and communities. By monitoring Mesonet stations near active fires, incident commanders can better anticipate these shifts, improving the chances of containing fires quickly and safely."

Being able to stage a single-engine airtanker in the area of highest wildfire risk can mean the difference between a small, contained fire and a devastating, large-scale event, he said. The Nebraska Forest Service also uses Mesonet data to decide the best time to replant trees destroyed in fires.

"Without this data-driven approach, seedling survival rates would be lower, costing both landowners and the state valuable time and resources,” Erixson said.

In the future, cameras on the Mesonet stations could serve as an early warning system for wildfires, aiding in wildfire management and community safety, he said.

When speaking of new tools being added to the system, Behnke said Version 2 of the online data access tool is in the works. With the second version, users will have more options, like being able to get data for all the stations in a certain county or a Natural Resources District or at a certain quality control level.

Since being hired at the university in April 2023, Behnke has been applying for funding to put in new stations and maintain existing ones. He estimated it costs between $5,000 and $5,500 per year to maintain a Mesonet weather station. That includes costs like labor and travel to the sites.

"I don't think it's a terrible amount," Behnke said. "It's just that people need to be shown the value. Anybody who uses that data, for example, to get a disaster relief check knows the value."

The Natural Resources Districts support 28 stations in the state now, he said, and the eight new stations funded by the USDA Farm Service Agency provide additional data which farmers, Natural Resource Districts and other users rely on.

Dennis Schueth, general manager at the Upper Elkhorn Natural Resources District, said his district uses the stations to determine total evapotranspiration data to help producers compare the amount of irrigation water applied versus crop water use to determine their irrigation needs. The producers they work with also use data from the stations to fill out nitrogen and irrigation forms submitted to the district.

Schueth said the district provides its board of directors with information from the stations and uses the data with local, state or federal agencies in modeling weather trends. Overall, he said the Mesonet has been a positive network to be involved in.

"With all the different types of weather applications that are available, some individuals think they can just look at that weather app and they forget some of that information is provided by the Mesonet stations," he said.

Other station networks across the state, such as those at airports and volunteer weather observation stations, have limited coverage and observation capabilities. Mesonet stations provide a wider range of data, including soil observations and solar radiation, and take images of the weather. This allows the Nebraska Mesonet to develop data tools specific to user needs.

Behnke said that with the growth of the Mesonet in Nebraska and the demand for ever increasing data observations, the Mesonet will need a consistent funding stream to maintain the stations.

Larkin Powell, director for the School of Natural Resources, said he has been working toward establishing that stream.

"Our Nebraska Mesonet team has met the challenge of adding stations in key gaps throughout the state," he said. "I have prioritized the Mesonet's need for continued operational funding as we work with our partners."